Reading the Migration Library is a project that takes an unbounded approach to migration as well as creative methods. Aside from the method of making a book-like publication that is constrained to the size of a quarter-letter page, RML includes storytelling, poetics, abstraction, historical accounting, interviews, critical studies, and other approaches. The effectiveness and impact of each approach has been considered carefully by the artists and poets whose ideas have found their way onto the small pages of RML publications.

Storytelling from lived experience of migration, in creative projects and research projects, comes with risks. The outcomes risk entrenching polarized positions, by landing on the wrong listener (or audience), for instance. Migration stories need the care of communities. But looked after in that way, they can help people with lived experience to find each other and find validation. The method of storytelling must not be rushed, and its outcomes must not be pre-determined. And, there are migration experiences that cannot be “narrated”. There needs to be an understanding that not every story or lived experience needs to be spoken or published.

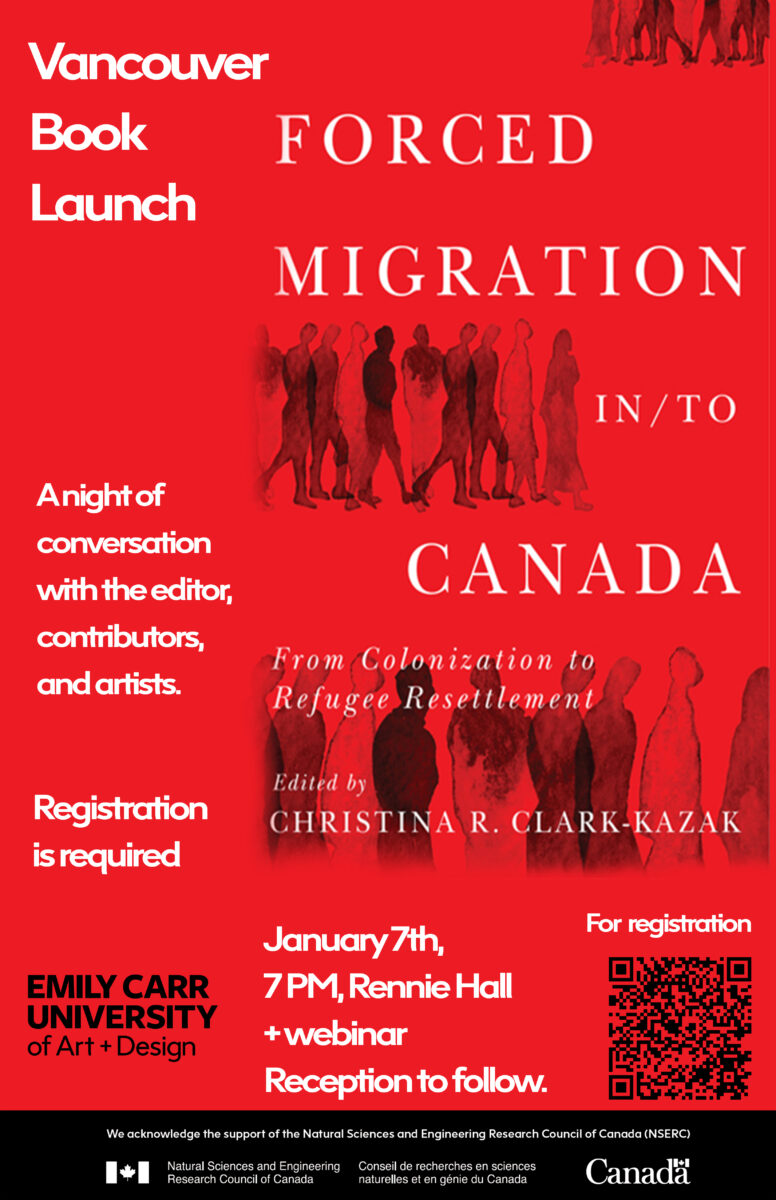

These storytelling truths were described by contributors to a panel that I was moderating at the Vancouver launch of the book Forced Migration In/To Canada in Rennie Hall at Emily Carr University of Art + Design (January 7, 2025). Alongside the book’s contributors, Erin Goheen Glanville and Francisco-Fernando Granados, local presenters artist Aaniya Asrani and researcher Soodabeh (Soodi) Joolaee provided these valuable and diverse perspectives on storytelling as a method in migration work. They came in response to a question posed by audience member Gabriele Dumpys Woolever (Research Manager, UBC Centre for Migration Studies) who noted the “incredible value” of focusing on lived experience and storytelling in research and art, and asked what are its “challenges, limits and possibilities, and who is [its] audience?”.

Since the responses so clearly and creatively described a few of the key considerations in the use of storytelling in migration studies and art, I sought out and received permission from the panelists to transcribe them here.

Erin Goheen Glanville – I [feel your questions] really resonate, Gabriele. I think I’ve become less and less interested in what stories can do. I feel like that is where my research started. And [now] I’ve become more and more interested in how communities can care for stories well. And I think it is remarkable how energizing it is to move out of a space of learning and information-sharing and into a space of just acting with two or three other people. Like the enormous amount of hope and energy that comes just from that interpersonal connection. That connection of rage, or the connection of love for something. Small acts –it is so cliché –but the tiniest of actions, are actually what shifts something for me. And moving away from thinking of stories as tools and thinking more about them as gifts that are held by a community in a particular way, and then motivate a community, however big or small, to kind of live into or against that story.

Soodi Joolaee – I want to add a little bit by commenting that actually sharing our stories, sharing our lived experiences with others, it actually creates a kind of connection between people. It helps to build [us] along. [Through them] you know there are other people with somehow similar stories or experiences –or different experiences, that these differences or similarities can connect people to each other and make them feel that they are not alone, and that there are other people that have experiences that weren’t shared or weren’t heard.

Aaniya Asrani – Great question. It is something that I have struggled with as a storyteller, as someone who is talking to other people about their lived experiences in the hopes that it can do the most. I think about urgency vs slowness and how they both have different functions. So with everything that is happening now with the ongoing genocide in multiple places in the world, I am thinking about how we consume it in its immediacy vs how we consume it slowly over time, and what that looks like over time in terms of story. I think for example about Joe Sacco who is an illustrator who has been writing books about Palestine for a long time, and how that has informed generations and how they perceive more. Yeah, and just thinking about how different modalities have different functions. Obviously one story has immense power but we cannot expect one story to do everything. But I think what [has already been] said [on this panel] is so important, the sharing of the story together. That becomes the audience, the people in the room with you –the people who will resonate and feel less alone.

Francisco-Fernando Granados – I would add that in the importance of and the vitality of – in the possibilities [that are inherent] in narrating [stories of migration], there also exists a broader context where we have to acknowledge the limits of narratability, the limits of what can be narrated. In fact, some of us – [pause]. You know, I feel peace [because] my work mostly deals with the limits of what can be narrated. In the visual arts, one name we have for that is “abstraction”. I can do the work of abstraction in peace knowing that there are so many great people working on narration/narratives, its possibilities, and know how to do so ethically. But I think it has to be – we have to [recognize that] it exists in a context where we acknowledge it exists in a context where there are [things that are] unnarratable, unspeakable, unfathomable – in each direction. In the direction of grief and rage, and in the direction of joy and pleasure. Something that was an intuition that we [points to Lois Klassen] were thinking of that didn’t necessarily make it into our chapter was something Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak says which is that the ethical interrupts the epistemological. This means to me that there are things which we cannot render as an object of knowledge because to do so—the violence of doing so—would be such that we [would] need to understand where that line is. It is about [our responsibility to know the limits of the] expanded field of narratability.

~

Thank you to panelists for allowing me to publish their comments in this blog post. The recording which resulted from including an online audience (through zoom) was circulated to those who could not attend, but was not made publicly accessible.

The event’s panelists were,

Aaniya Asrani is a Vancouver-based interdisciplinary artist, graphic designer, and visual storyteller from Bangalore, India.

Soodi Joolaee is a Research ethics and regulatory specialist with Fraser Health Authority in Canada, and an accomplished researcher and Professor of Nursing from Iran.

Christina Clark-Kazak is a Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of Ottawa. Clark-Kazak edited the book Forced Migration In/To Canada and authored the introduction.

Erin Goheen Glanville is a community organizer and spiritual caregiver (a.k.a. Lead Pastor) at Artisan in the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver. Goheen Glanville co-authored with Efrat Arbel the chapter “Labels, Discourse, and Meaning-Making”.

Francisco-Fernando Granados is a PhD student in the Media & Design Innovation program at Toronto Metropolitan University, and a former contributor to Reading the Migration Library. Granados co-authored with Klassen the chapter “Reflecting on Ethics in Forced Migration Research”.

Lois Klassen (moderator) is a coordinator of the Emily Carr University Research Ethics Board and Adjunct Professor at the School of Interactive Art and Technology, Simon Fraser University, and the artist host of Reading the Migration Library. Klassen organized and hosted the Vancouver launch with support from Ece Arslan and the NSERC “EDI Capacity Building Grant” at Emily Carr University.

Forced Migration In/To Canada is available for download here.